Let’s face the facts.

Despite laudable international initiatives for climate change mitigation and environmental preservation [i], major changes in Earth’s balances have been set in motion and we’re starting to experience their consequences: heat records; increased droughts; increased wildfire intensity and frequency; melting of landlocked ice; increased sea level and coastal storm damages; ocean acidification; climate change-based migration flows of human and animal/insect populations, along with pathogens and diseases—without considering the great loss in biodiversity, where one animal or vegetal species disappears every 20 minutes.

Habitat loss is the main cause of biodiversity loss, and a main cause of habitat loss is land use change due to urbanization and transport infrastructure.

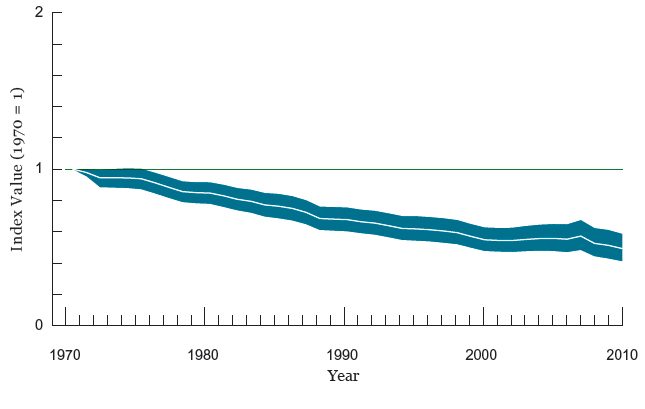

Indeed, when the debate is focused on “energy efficiency” and “greentech”, we’ve almost forgotten one major threat for human survival: the survival of all the other inhabitants of our planet. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, the extinction rate is between 100 and 1,000 times greater than during the 65 million (!) previous years. As a result, 26,000 (known) species disappear each year, and according to the Living Planet Index 2014 [ii], “population sizes of vertebrate species—mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish—have declined by 52 percent over the last 40 years”; that measure is up to 76 percent for freshwater species. According to the IUCN, the picture isn’t rosy for the near future: 25 percent of mammals, 13 percent of birds, and 41 percent of amphibians will disappear in this timeframe, adding to 37 percent of all known species by 2050.

Why should you care, if you’re not an enthusiastic nature conservationist?

For three reasons at least:

Firstly, species—from bacteria and viruses to mammals, including humans—are part of the “web of life”, as Fritjof Capra [iii] writes it. “These are the living forms that constitute the fabric of the ecosystems which sustain life on Earth”, says Marco Lambertini, WWF’s International Managing Director.

See also this, on biomimicry as a key path forward.

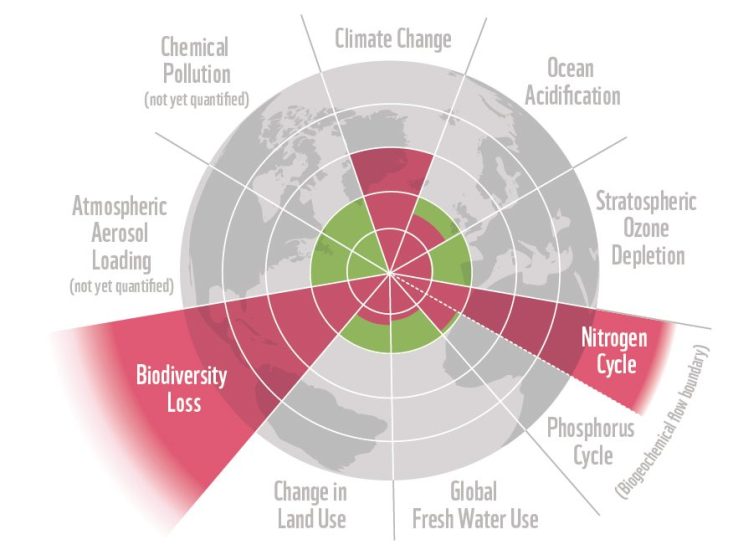

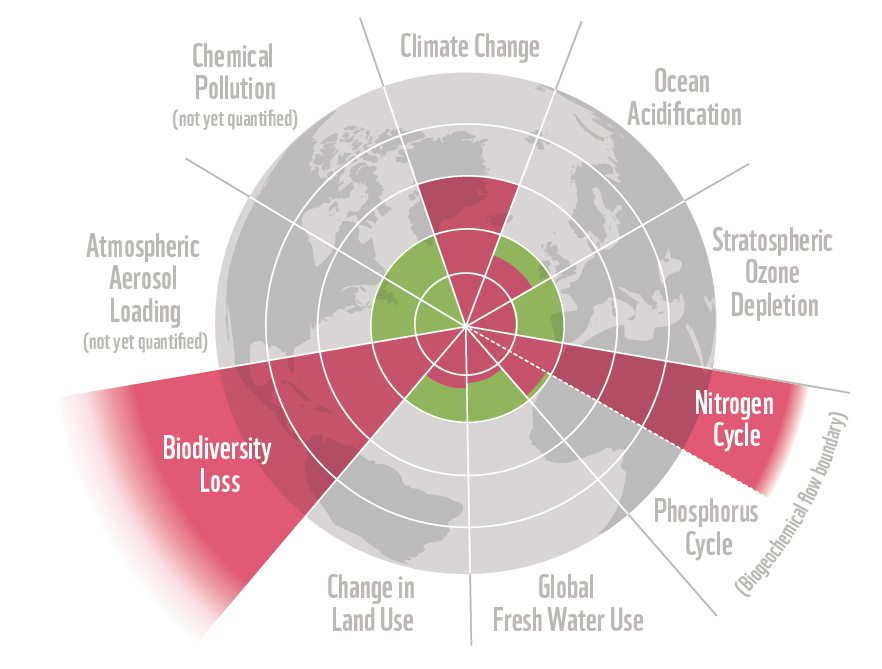

On a global level, where all those interactions add to biochemical and geochemical cycles (such as the nitrogen, water, carbon, oxygen, and phosphorus cycles), they have historically maintained the delicate balance of Life. Therefore, biodiversity, from genes, to species, to ecosystems, is paramount to the presence of life on our planet, and to our own survival, notably through all the ecological services it provides [iv].

Despite our great effort to disconnect ourselves from the “web of life”—to the extent that we are investing billions into inventing artificial life-support systems for space exploration—we, human beings, continue to be inextricably tied to this web of life.

Secondly, because we human beings are the main threat to biodiversity and our environment, so, therefore, are we our main threat to our own survival.

Indeed, the primary explanation for biodiversity loss, according to the Living Planet Index, is the degradation, fragmentation, or loss of natural habitat (45 percent), followed by the over-exploitation of resources (37 percent) and climate change (7.1 percent only). Habitat loss is identified as a main threat to 85 percent of all species described on the IUCN’s Red List. Habitat loss is mostly caused by the expansion of agricultural land; intensive harvesting of timber wood for fuel and other forest products; and overgrazing. “Around half of the world’s original forests have disappeared, and they are still being removed at a rate 10x higher than any possible level of regrowth. As tropical forests contain at least half the Earth’s species, the clearance of some 17 million hectares each year is a dramatic loss”, says the Living Planet Report 2014.

But the second main cause for habitat loss is land use change due to urbanization and transport infrastructure. We’re generating a quantity of artificial soil as big as the area of Greece every year. In the European Union alone, such land use change represents 1,000 km2 each year, or 275 hectares per day [v], of artificial soil—the equivalent of Central Park in New York City, or the area of Hungary within one century. Alongside urbanization comes air (and also sound and light) pollution, accounting for 4 percent of biodiversity loss.

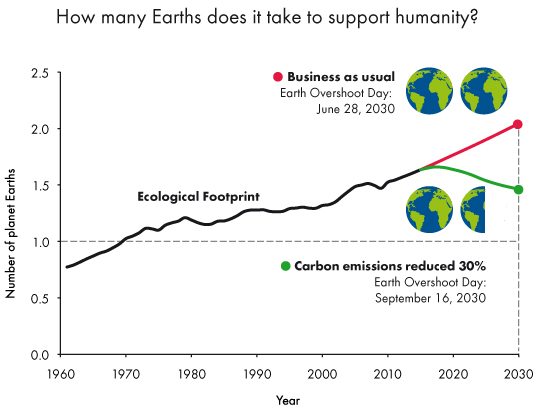

The Global Ecological Footprint [vi], published each year by the Global Footprint Network, is a very clear and understandable signal measuring our pressure on our planet’s resources and “biocapacity”: we are using more natural resources than our natural environment can provide, and we would need 1.5 Earths to fulfill our consumption needs (and up to 4 Earths if we all had the living standards of U.S. citizens).

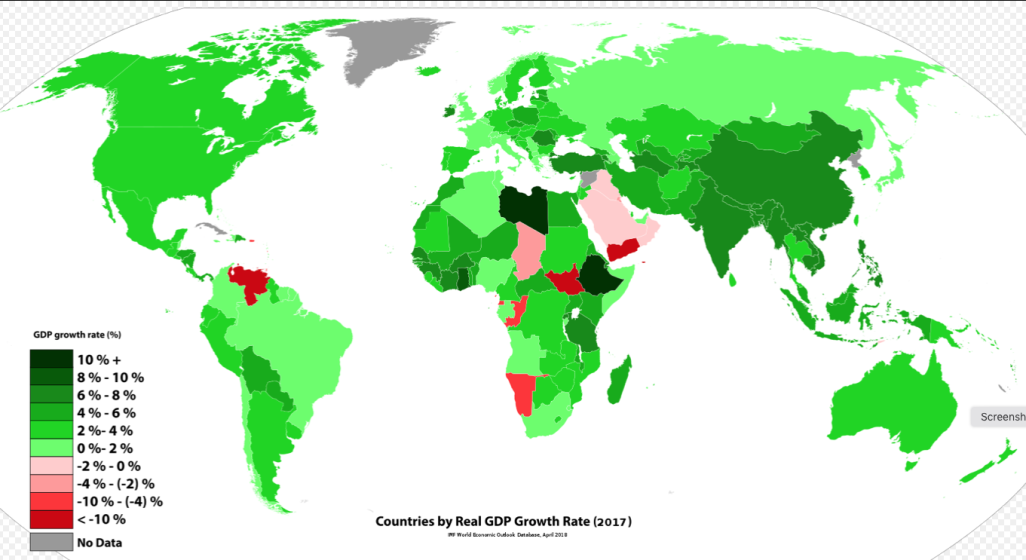

With the phenomenal growth of the world’s population, which has added 2 billion people since 1990 and is expected to add 4 billion more by 2100 (3 billion for Africa alone); with the growing concentration of this population in urban areas (from 30 percent of the global population in 1950 to 66 percent by 2050), especially in Africa; with the rise of new economies; and with developing countries seeking the average standards of living in the West, the pressure on our planet is not going to ease.

Experts believe we entered the Anthropocene epoch in the mid 20th century, and our planet is paying the price. As the climate experts from the IPCC noted in their 2007 synthetic report: “Unmitigated climate change would, in the long term, be likely to exceed the capacity of natural, managed, and human systems to adapt. (WGII 20.7, SPM). This description does not even name the biodiversity loss and nitrogen cycle threats that are identified by the Stockholm Resilience Center as the major Earth boundary overshoots, out of ten such factors.

To put it more directly, we’re heading toward the wall at full speed, still wondering and discussing how we can slow down; we now have to prepare ourselves for damage (crash?) control, as well as resilience (survival?).

Thus, the third reason we should care about biodiversity is that it might be the solution to our problems. See my next post for details on how using biodiversity could help us achieve sustainability and resilience.

Olivier Scheffer

Paris

For more information on this subject, read:

“Ecomimicry: Reconnecting Cities—and Ourselves—to Earth’s Balances” on TNOC.

References

[i] the latest being the Paris Agreement at the COP21 – if ratified by 55 countries representing more than 55% of GHG emissions

[ii] “Living Planet Report 2014” from the WWF, the Zoological Society of London, The Global Footprint Network, The Water Footprint network http://www.worldwildlife.org/publications/living-planet-report-2014

[iii] http://www.fritjofcapra.net/books/

[iv] The United Nations Environment Programme made this very clear more than 10 years ago in its Millennium Assessment programme : supporting services (nutrient recycling, primary production, and soil formation), provisioning services (food, raw materials, minerals, water, energy, genetic, and medicinal resources), regulating services (climate regulation; carbon sequestration; waste decomposition and detoxification; purification of water and air; pest and disease control), and cultural services (recreational, therapeutic, educative, historical, spiritual).

[v] « Lignes directrices concernant les meilleures pratiques pour limiter, atténuer ou compenser l’imperméabilisation des sols », Services de la Commission Européenne (2012)

http://ec.europa.eu/environment/soil/pdf/guidelines/pub/soil_fr.pdf

[vi] http://www.footprintnetwork.org/en/index.php/GFN/page/world_footprint/

Leave a Reply