When I see titles like this, I always wince. Half-baked, hastily-gleaned, Internet-trolled info-news parading as something useful; it’s everywhere, and it’s only ever there as time-wasting click-bait. It all lives in the land of hyphenated-nowhere that delivers most of what we now think we know about the world. But I won’t let that stop me. Ecocities are important.

There are ecocity definitions that have both vision & practical purpose, which have been debated & tested for over three decades—let’s use them.

- Defining an ecocity—what is it?

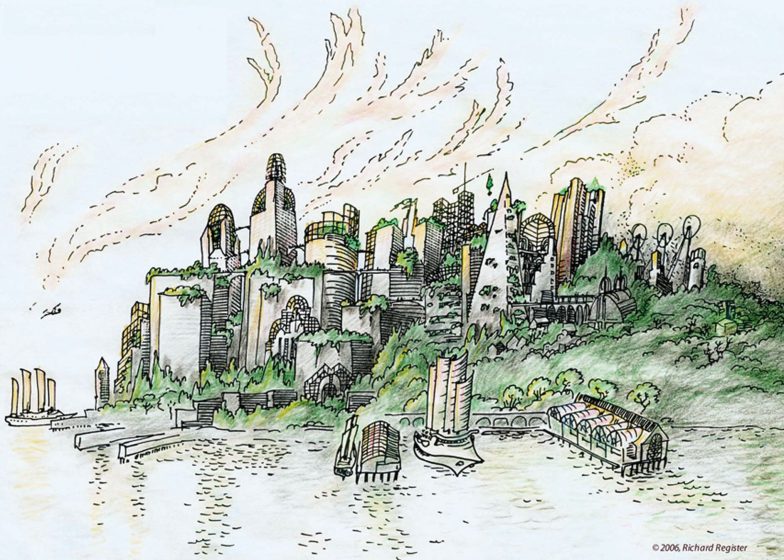

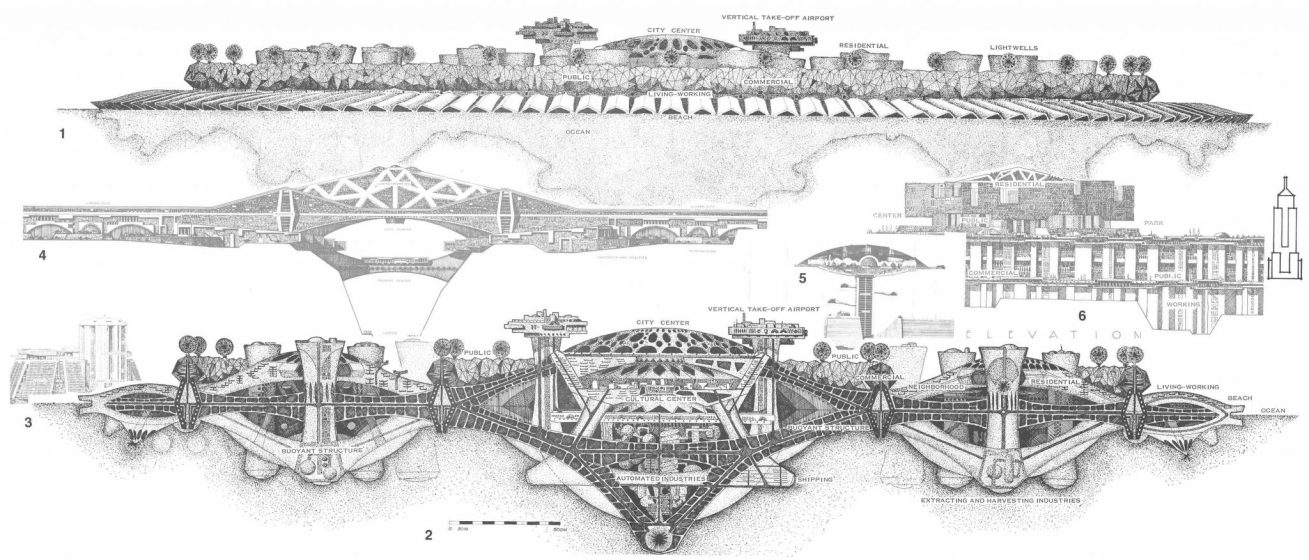

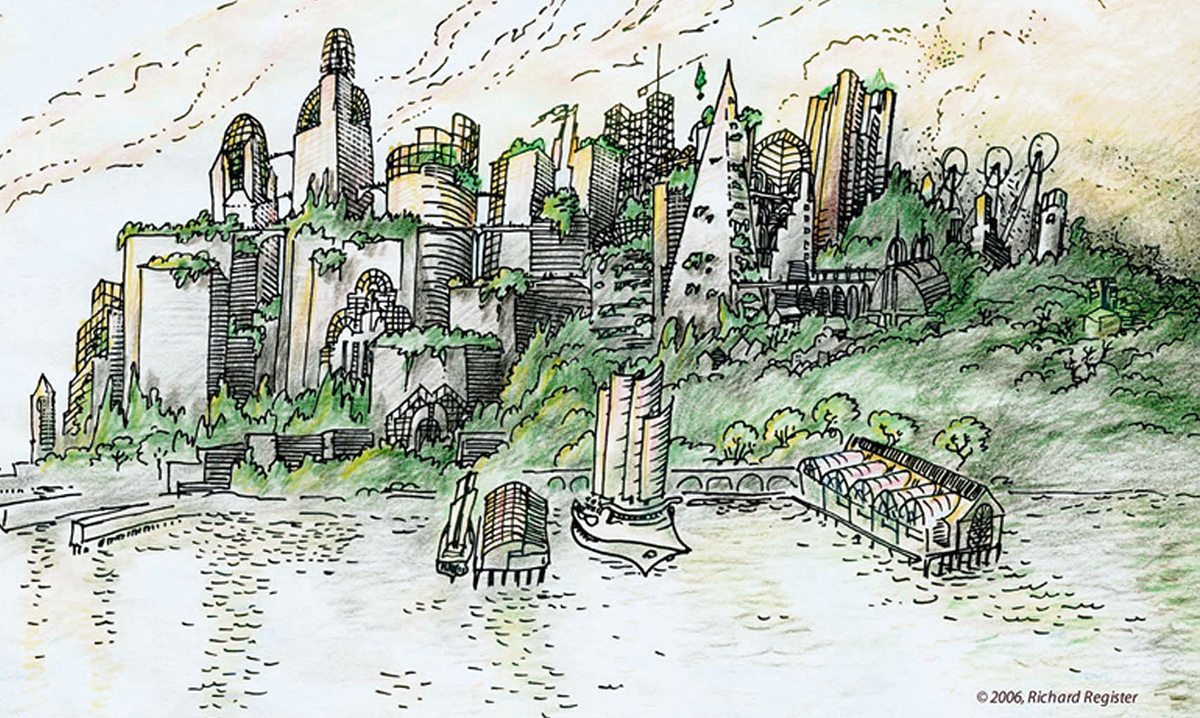

There are, and have been, many interpretations of the ecocity concept [see illustrations]. At the time I first started talking about ecocities, it was usual to hear the term dismissed as an oxymoron. I suspect that the number of people who think they know what “sustainable” means greatly outnumbers those who are familiar with the “ecological” variant of city ideas, and I thought it was high time I tried to clarify some of the basics. The Wikipedia entry on “eco-cities” provides a rather rambling mish-mash of what comprises an ecocity, but although there is probably nothing in it that is actually “wrong”, it lacks any sense of visionary purpose. For that, it’s hard to go past Richard Register’s definition in “Ecocity Berkeley” (the first book in English to have “ecocity” in its title), in which he writes, “An ecocity is an ecologically healthy city”. Those seven words set out a powerful and challenging agenda, begging as many questions as it purports to answer. With the brevity and pertinence of a koan, Richard’s next four words speak volumes more: “No such city exists.” (Register 1987 p. 3)

An ecocity is about ecological health. It is conceived in aspirational terms because we don’t yet know even half of what we need to know to make the concept real. Although we don’t know enough about how the world works, the assertion of the ecocity is an article of faith that once the idea becomes strong enough to set development and political agendas, provided it is understood amongst the wider community and people can engage with it and live the idea, the system of knowledge we call culture can begin to create ecocities. As Register says, “the concept must be firmly established and broadly understood and supported”. It’s not only about creating “the ‘sustainable’ city that coexists peacefully with nature”, it’s about “a new creative adventure accessible to everyone” and “nothing less than a new mode of existence and creative fulfillment on this planet” (p.5). In this view, an ecocity is about very much more than solar powered trams, energy-efficient buildings, and fewer cars (even if they’re electric).

Thirty years on from the publication of Ecocity Berkeley, it is not always easy to sustain the optimism and hope that the task of promulgating the ecocity meme demands, for these are, as Richard insists, “dark times” (Register 2017, personal communication).

- International ecocity conferences have been running for almost three decades

There have been many “ecocity” and ecocity-related conferences in the past several years, but there is only one Ecocity Conference Series. Renamed Ecocity Summits in recent years, this is a conference series that started under the helm of Richard Register in Berkeley, California, in 1990.

The conferences have always been about bringing together diverse voices with a passion for issues and ideas that are essential to making ecological cities and taking the ecocity vision to the streets. The early conferences, in particular, were characterised by a degree of eclecticism that was suited to the creation of the kind of multi-facetted and fascinating places that early ecocity protagonists imagined ecocities would be. The first conference included a dazzling range of speakers and thinkers (not all American) that included David Brower, original founder of Friends of the Earth, and Ed Mitchell, the sixth man to walk on the moon. There have been 11 conferences in the series to date, hosted on six continents with the deliberate aim of moving north to south, developed to developing country, seeking a wide, culturally inclusive platform to share and disseminate ecocity theory and practice.

Al Gore was invited (under the auspices of Richard Register) to be lead speaker at the Second International Ecocity Conference in 1992 in Adelaide, Australia (see photocopied fax). He was unable to attend at the time but now, 25 years later, he is the confirmed principal at the forthcoming Summit in Melbourne, Australia.

The International Ecocity Summit/Conference Series

• 2015 Abu Dhabi, UAE

• 2013 Nantes, France

• 2011 Montreal, Canada

• 2009 Istanbul, Turkey

• 2008 San Francisco, USA

• 2006 Bangalore, India

• 2002 Shenzhen, China

• 2000 Curitiba, Brazil

• 1996 Yoff, Senegal

• 1992 Adelaide, Australia

• 1990 Berkeley, USA

- A smart city might not be an ecocity

A smart city is all about using technology to capture, interpret, and employ the data generated by urban systems to make those systems, and thus the city, more efficient. Is an ecocity a smart city? It can be, but, in the sense that “smart city” protagonists use the term, it certainly doesn’t need to be, unless you accept the definition broadened to include sentient, carbon-based, bi-pedal life forms as integral to the operating system.

Smart city agendas invariably refer to improving the quality of life of people, but rarely mention the need to maintain the quality of life for other denizens of the planet.

In summary, an ecocity does not have to be a smart city, but a smart city can aspire to becoming an ecocity.

- Biophilic and ecological cities are not necessarily the same

As the leading advocate of “biophilic cities”, Tim Beatley might argue otherwise, but, whereas an ecological city must acknowledge and fit with nature, it doesn’t necessarily follow that it operates so that the citizens have a sense of biophilia—although it is most likely that it would, and it is hard to imagine creating a city “in balance with nature” if nature wasn’t celebrated for its own worth. Likewise, a biophilic city may be ravishingly attractive but, in theory, it could be supported by fossil fuels and produce streams of toxic waste (i.e., be a conventional, current-day city with biophilic overlays—see my last TNOC blog for a brief discourse on what is “authentic” in biophilic experience).

- Sustainable cities and ecological cities are not the same

You’re probably beginning to get the theme here. Twenty-five years ago at EcoCity 2, I prompted some real distress on the part of some very strong advocates of “sustainable cities” by insisting on there being a difference between what they were talking about and what I understood by the idea of an ecocity. Hair-splitting infests all professional and academic endeavours, so it may not be surprising that, with sufficient effort, one can argue a chasm of difference between two very similar ideas. My argument rested on my fear that “business as usual” was quite able to assimilate the incremental improvements that were being advocated to move “towards sustainability”, and thence appropriate the tag of “sustainable” without there being any qualitative shift towards anything like an ecocity. I’m inclined to rest my case on the 25 years of history that have failed to deliver anything remotely like a real ecocity, but there have been some significant improvements in urban systems performance around the world and urban experiments such as Masdar in the UAE that have to be welcomed.

- Ecopolis isn’t a brand, it’s a theoretical position

Ecopolis appears to be just another word for ecocity, but it harbours some profound, albeit subtle, differences. Simply put, the concept of ecopolis (that I favour and have promoted publicly since 1989) is broadly shared by Russian, Chinese, Italian, and other European researchers and protagonists and refers to a “city plus its region”. Thus, an ecopolis is not just bricks-and-mortar, steel, glass, and concrete, but includes its essential hinterland. Its ideal model would be that of urban systems embedded in their bioregion in an interdependent relationship.

From “eco”, to do with ecology and “polis”, a self-governing city, I take ecopolis to mean city plus region (like Magnaghi and Wang) but that clearly isn’t the definition adopted by Vincent Callenbaut who would have well-heeled “climate refugees” living on self-contained, hi-tech ocean-roaming Lilypads each claiming to be an “ecopolis”. Register prefers ecocity to ecopolis, arguing that as a word it is more readily understood (and is easier to render in the plural). To include the region, he favours “ecotropolis”. But we’re all trying to say pretty much the same thing.

The various terms in use can be confusing—is a book about sustainable cities also a book about ecocities, even if the word ecocity is barely acknowledged? The most important thing is to be a little bit tedious and, in any discourse on the subject, begin by making plain what definition in terms you are using.

- Ecocities die

All cities change, grow, shrink, live, and, eventually, will die. To quote myself:

“Although the science of cybernetics and systems theory allows that cities might be considered organisms, it may be more correct to say that a city is not an organism, but it is alive. The ‘city as organism’ is a useful and powerful metaphor, but ‘city as ecosystem’ is not a metaphor. It is an entirely appropriate and scientifically defensible description. A city is a massive constructed device that integrates living and non-living components into a total living system that is a physiological extension of our species. It only lives when it is occupied, and it can die. Dead cities are the subjects of study by archaeologists, who can discern a great deal about their living state from the condition and disposition of their carcasses and bones, whilst an analysis of the land around them tells much about the way they lived and the impacts from their reach into the hinterlands.” p.357

Cities outlast empires, even those to which they are central and essential. The Roman Empire lasted about 1,500 years, but the city of Rome has been continuously inhabited for longer than the empire that carries its name. Argos, in Greece, has probably been continuously inhabited as “at least a substantial village” for the past 7,000 years, and Damascus in Syria and Beirut in the Lebanon have existed for over 5,000 years.

All living things die. If a city is to be regarded in any sense as a living system, then it too will have a lifespan. It may reproduce and continue the essence of its existence even if virtually all trace of its original form is lost. Jericho, for instance, can be dated in several “layers”, but the building up of the layers that archaeologists study doesn’t happen as a set of palimpsests. Everything that went before provides an armature, or the DNA, if you will, on which the new is constructed.

Taking sides?

Ecological, biophilic, sustainable—we’re all basically on the same side, and that is important—but some of us remain deeply frustrated by the continual slide towards global ecological collapse and feel compelled to be a little more insistent about the need for much more rapid change. Some extreme discomfort is integral to that proposition. Better to speed that up lest the extreme discomfort get bottled up and explode dangerously—and too late to stop the disaster of global ecological collapse on a +6 degree Celsius planet.

“Ecocity” is an aspirational label. But in the modern world, that has more than one interpretation. For the “true believers” in the idea of making cities that are both measurably and poetically in balance with nature, it encapsulates an enormous amount of meaning and, for them, merely stating the idea of an ecocity implies an agenda for society, culture, economics, and government with a vision and intention for action that stretches indefinitely into the future. For the less committed, it is simply a cynical branding exercise.

Why does any of this matter? Well, if two people are talking about what they think is the same thing and it isn’t—or if they talk about the same things as if they were different, but they’re the same—you have a recipe for confusion and misunderstanding. Terrific if you’re out to scam people, but of no value to any serious efforts to build human habitat for an ecologically healthy future.

To summarise, if there are ecocity definitions that have both vision and practical purpose, which have been debated and tested for over three decades—let’s use them and be critically cautious of anything less. Whilst recognising that a smart, biophilic, or sustainable city may be an ecocity, even an ecopolis, it is clear that there are distinctions and, for clarity at least, they should be acknowledged. After all, cities may boom and bust through lifecycles that transcend empires and politics but—in one form or another—the nature of cities lives on.

Paul Downton

Melbourne

Leave a Reply